|

|

FLIGHT INTO HISTORY

EARLE OVINGTON WAS FIRST

|

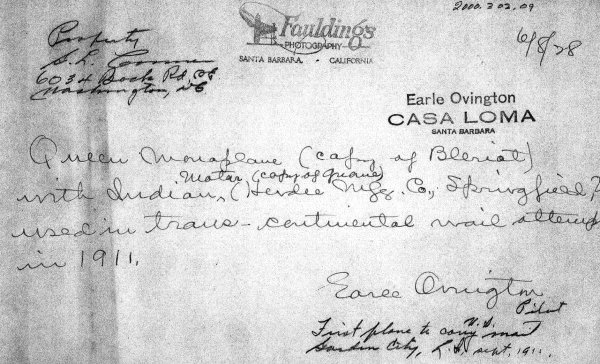

September 23, 1911, dawned gray and cold. Despite the chilly air and metallic skies, 10,000 spectators thronged to Long Island’s Garden City Estates for the big international aviation meet. The Nassau Aviation Corporation of Long Island had obtained the use of the airfield, located on Nassau Boulevard near Garden City, from the Aero Club of New York. Some of the crowd arrived by a train commissioned especially for the gala occasion, while others motored out Nassau Blvd. Many ladies totted stylish Japanese parasols and some donned blue and green aviators’ goggles. A snappy-looking band in red coats and caps played lively tunes. While the freshly painted bright green bleachers filled, 36 noted flyers from England, France and the United States readied their planes for takeoff. Among them was a young man sporting a wide smile and a determined glint in his eyes. He wore knee-high leather boots, knickers and a French crash helmet that resembled an English riding hat, and he puttered about his machine. To a modern eye, his craft looks like a large winged tricycle, but aviation enthusiasts of the day recognized it as a American-made Bleriot Queen tractor-type monoplane, similar to the first aircraft later built by Clyde Cessna. He and a French mechanic had brought it to the U.S. At the time Ovington believed the French made aircraft superior to those made in America. Appropriately he named his graceful craft Dragonfly; it bore a bold number 13 on its rudder, and the pilot’s little mascot-doll named Treize (13) dangled from its see-through fuselage. No novice to air competitions and no stranger to walking off with prize money, Dragonfly’s pilot, Earle L. Ovington, had gained fame throughout northeastern United States as a skilled pilot. Among his credits, he flew the first plane over Boston and also parts of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island and pocketed $5.900 for a sixth place showing in a tournament in Chicago. Ovington learned his skills at Bleriot’s Aviation School in Pau, France. Prior to his training, he worked as an engineering assistant to Thomas A. Edison in New Jersey.

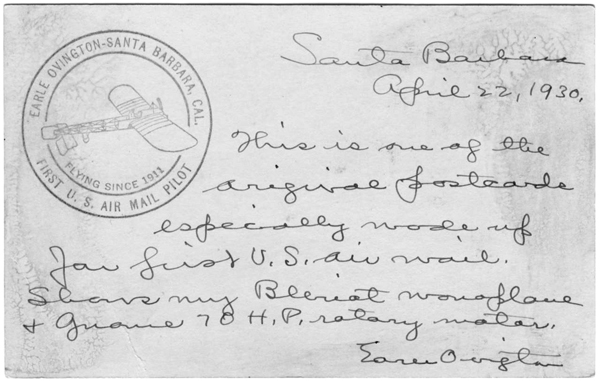

Did Ovington sign up for the Garden City competition hoping to become the country’s first airmail pilot? The answer may never be known, but it is known that when the organizers of the meet asked for a pilot to carry the mail that day Ovington stepped forward. It mattered not to him that the airmail experiment offered no remuneration. Perhaps, he saw immortality winging his way. His wife, Adelaide, remembered that when he heard that Gov. Woodruff was looking for someone to carry the mail, he asked, "Is this the first time it has ever been carried in America?" U.S. Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock had long considered aeoplanes a prime vehicle for transporting mail. As early as November 1910 he approved a ship-to-shore airmail experiment, but bad weather squelched one attempt and a broken propeller crushed a second effort. Not one to give up, when Hitchcock learned of the forthcoming trials at Garden City, he convinced organizers to include an experimental mail trial. On the day of the big meet, spectators found 20 collection boxes situated near the grandstand and surrounding areas and saw a large white tent with U.S. Mail/Aeroplane Station No. 1 in large letters emblazoned on its top. Ovington was duly sworn in as the first U.S. airmail pilot, then handed a load of 640 letters and 1,280 postcards in a mail bag. With hardly enough room in his little cockpit to hold the bundle, he tucked it between his legs and at 5:26 p.m. took off. In flight he balanced it on his knees so he could steer with his feet. Five and a half miles later, a distance he covered in six minutes, he arrived over Mineola. His wife remembered that he had sworn to "guard and protect" the mail, and so he did to the best of his ability. He circled at 500 feet, took aim, tossed the bag over the side and hit the mark dead center, but the sack burst on impact, scattering letters and postcards thither and yon. Rapidly retrieved, they were sent on their way by regular post. Except when weather intervened, Ovington flew at least one load of mail each day until the end of the meet. After that he attempted to be the first to fly transcontinental, but he was forced to abandon that inaugural flight because of engine trouble. Ovington deserves his place in aviation history as America's first airmail pilot.

|

|

Postcards front and back courtesy of Harry McConnell looking for museum collection to donate postcard. hmcconnell@mac.com |

History |

Air Mail Pilots

|

Photo

Gallery |

Flight Info

|

Antique Airplanes

|

Members |

|

copyright © 1999 Nancy Allison Wright, President Air Mail Pioneers

|