|

|

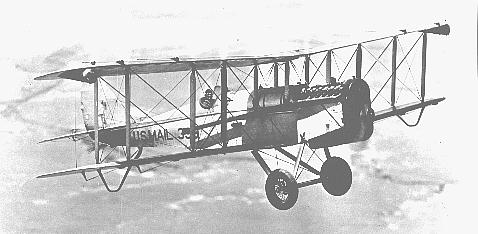

PHOTO: Ernest M. Allison, unsung hero of the first day/night transcontinental, smiles proudly from his personalized de Havilland-4B. Dirty gray clouds rolled in low over Long Island Sound, a sure sign of bad weather ahead. U.S. Air Mail Service pilot Ernest M. Allison lowered his aviator's goggles and fastened his sheepskin-lined helmet. He signaled his mechanics to pull the chocks from under his wheels, then he eased open the throttle on the de Havilland-4B (DH-4B), sending it surging to life. Smoke swirled from the World War I surplus bomber's exhaust, enveloping bystanders in a cloud of noxious fumes. Waving a cheerful farewell to well-wishers, he taxied across the airfield. Turning into the wind, he opened the throttle fully, and skimmed along the runway. His tail skid lifted, and in a moment pilot and biplane, carrying 350 pounds of mail bound first for Cleveland then for points west, as far as San Francisco, disappeared into the early morning gloom. The time was 6:14 a.m. The place, Hazelhurst Field, Mineola, Long Island, and the date, February 22, l921. Ten minutes earlier mail pilot Elmer G. Leonhardt also had taken off from the same field. On the other side of the continent, U.S. Air Mail Service pilots Farr Nutter and Raymond J. Little lifted their de Havillands from San Francisco heading east toward the sun, much of their commemorative airmail addressed to New York.

PHOTO: By the time this photo was taken at the Omaha, Nebraska, airmail field in 1921, Elmer G. Leonhardt's DH-4B number 157 had force-landed four times. One incident, which made world news, occurred on the first day of the first day/night transcontinental. Photo courtesy of the United States Postal Service. Thus began the first day/night U.S. transcontinental flight, the world's first scheduled long distance flight - New York to San Francisco. Nineteen ninety-six marked the 75th anniversary of that aviation milestone, the first time in history that airmail was carried between points at an announced time, irrespective of weather or time of day. That day and the next U.S. Air Mail Service pilots flying wire-braced, open-cockpit biplanes established a pattern that evolved into the present global air transportation network. Since September 8, 1920, the service had flown the mail from New York to San Francisco during daytime only, transferring it to trains at night. As a result, elapsed time, should weather or mechanical difficulties not intervene, was 72 hours at best, or a mere 36-hour saving over the fastest all-rail trip. Congress was not impressed. Having supported the airmail service from its fledgling startup period in 1918 through its first three tenuous years, lawmakers hesitated to appropriate additional funds to expand the service. "What good is the airmail?" asked Representative Jasper Napoleon Tincher of Kansas (Republican), "It can only carry a shirttail full of mail." What was needed was a dramatic demonstration of airmail's potential. Assistant Post Master General Otto Praeger decided that a round-the-clock relay of mail from New York to San Francisco in the worst weather of the year would prove airmail's clear-cut advantage over surface mail. The test would entail night flying, something so new that many pilots "doubted that you could keep an airplane right side up in the dark," said Allison. To keep the mail moving, the 882-mile stretch from Cheyenne to Chicago would be flown in the dark, it would be the longest night flight ever made by civilian fliers. Doubts were many - the New York Sun editorialized that the flight was "homicidal insanity." Forebodings about the safety of flying the mail were not groundless. In the prior three years 17 airmail service pilots had died in crashes traced to mechanical or weather-related causes. Airmail pilots at the time virtually flew by the seat of their pants. Their instrument panel included a magnetic compass, affected by everything metal on the plane. And when the air got rough on an easterly or westerly heading it oscillated all the way from north to south. Mail pilots had an altimeter, an airspeed indicator, a tachometer and a water temperature and fuel pressure gauge. They flew low - peering over the side of their planes to navigate - skimming rivers, railroad tracks and towns.

PHOTO: Jack Knight, known as the hero of the U.S. Air Mail Service, tests a radiotelephone, available to mail pilots once the Post Office established regular day/night transcontinental service. Photo courtesy of United Airlines. "An instrument panel is just something to clutter up the cockpit and distract your attention from the railroad or riverbed you're following," said mail pilot Harold T. "Slim" Lewis. Barnstormers and plane-walking stunt pilots could stay on the ground when the weather looked grim. Not airmail pilots. They were the first airmen to fly to a schedule, and they took what nature offered, be it wind, storm, fog, snow or hell. All those conditions greeted the men who inaugurated continual coast-to-coast scheduled flying on George Washington's birthday, 1921. "Plenty of people were on hand to wish us clear skies and good luck that day," said Allison. "As it turned out we certainly needed luck and plenty of it." While eastbound pilots out of San Francisco were blessed with clear skies, Allison and Leonhardt faced the furies. Snow, wind and a cotton-like fog turned flying the New York to Cleveland run into a prescription for disaster. The long, low ridges of the Allegheny mountain range that run NE/SW along central Pennsylvania are no place for a safe forced landing. Fog, the airmail pilot's nemesis, frequently hangs low in its valleys. Heavy with brush, difficult to read from the air, susceptible to violent, capricious winds and weather changes, the "hell stretch" or Allegheny "graveyard" as pilots christened the humpbacked mountains, brought more airmail pilots to grief than any other part of the transcontinental route. This day Leonhardt's luck held, however, and he reached the refueling stop at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, 22 minutes ahead of Allison. Twenty-six minutes later, he was airborne again, ascending into a freezing mist. In short order, heavy layers of ice that had build up on his plane's wings and wires, disturbing the normal air flow and reducing lift, forced him down in a field near Du Bois, Pennsylvania. The forced landing badly damaged his tail skid and axle and thereby grounded him. Soon after passing Morristown, New Jersey, Allison's engine started missing. "It was touch and go if I could reach Bellefonte," he recalled. Coming in over Nittany Mountain, Allison spotted Bellefonte's mail field just east of town, designated by a large white circle. He glided in for a safe landing. While he slugged down a cup of hot coffee, the Bellefonte field crew warmed up reserve plane number 192. After takeoff, Allison discovered that the propeller on the reserve DH-4B was badly out of balance, causing the entire craft to vibrate excessively. "I was tempted to turn back and swap propellers with the plane I had just brought in, but because of the importance of the flight I kept on toward Cleveland," he said. The problem was later traced to a linen sheath that covered the propeller up to about 30 inches from each tip. (World War I de Havilland propellers often left the factory wrapped in linen to keep moisture off their laminated wood.) When field mechanics had installed the new propeller on the reserve plane they had neglected to remove the linen. In the rain and sleet, some of this protective casing loosened and peeled off. "It would have been all right if all of it had come off," said Allison, "But one tip retained enough linen to throw the prop out of balance." By the time Allison reached Brookville, Pennsylvania, the weather had closed in and a light freezing rain was falling. "The ceiling was so low I was forced to fly about 75 feet above the Allegheny River to avoid hitting the bluffs," he said. Weighted with ice, the DH-4B was unable, even on full power, to climb above a cable for transporting iron ore strung across the river; flying under the cable, the plane missed the obstruction by less than 10 feet. Now fast losing altitude, the DH-4B descended toward the ice clogged river. Suddenly, the plane shuddered as if struck by lightening and massive amounts of ice which had accumulated on the wings, struts and wires cracked, groaned and tumbled into the river. The incessant vibrations from the unbalanced propeller had dislodged the ice buildup and allowed Allison to gain altitude and continue flying. "That unbalanced prop saved me from going into the river at least three times during the 50-mile flight up the Allegheny," said Allison. Eventually the weather improved and Allison landed in Cleveland, numb with cold but proud to have "wangled the graft" (1921 pilots' slang for overcoming tough flying conditions.)

At this point airmail's future rested with the planes presumed to be flying eastward from California. Although good flying weather prevailed, the team from San Francisco flew part of their trip in predawn darkness. Leaving at 4:30 a.m., pilots Nutter and Little skimmed the fertile Sacramento valley east of San Francisco. Climbing to 18,000 feet, they crossed the snow-covered Sierra Nevada Mountains in early morning light, landing safely in Reno, Nevada, shortly before 7:00 a.m. From there, John L. Eaton and William E. Lewis, a fledgling mail pilot with only four months experience, scooped up the mail and took off with it toward Elko, Nevada. Following the railroad tracks across the Great Basin country, the two pilots reached their destination without incident. Eaton landed first, spent seven minutes on the ground changing planes, then hopped off to Salt Lake City. Lewis also changed to a fresh plane then followed a few minutes later. But at this point tragedy overtook the expedition. During a steep climb, Lewis's plane stalled at 500 feet. It went into a spin; Lewis lost control and the aircraft plunged to the ground. The young pilot, who was scheduled to be married the next month, died on impact. Although shocked and saddened by the news, post office officials, pilots, and field personnel hurried to fill the gap. Less than two hours afterward, Lewis's intact mail sacks (the busted bags had been gathered and sent to the post office for rerouting) were transferred to another plane, this one piloted by William F. Blanchfield, and flown to Salt Lake City. At Salt Lake City, Eaton, stepping out of his plane, learned that Lewis had crashed behind him. He turned his mail over to James P. Murray for that pilot's assault on the high mountain range to Cheyenne. An experienced pilot who'd spent all winter flying the high country, Murray easily droned over the rugged Wasatch and Laramie Mountains. As he completed his 381-mile run, pulling into Cheyenne's 6,100-foot-high airport at 4:57 p.m., darkness was descending. Now came the real test. Could pilots flying unheated, unprotected open-cockpit planes navigate the blackness of night in the dead of winter? To find their way through the darkness, pilots could use their magnetic compasses, corrected for wind. For a visual fix on landing, they could touch off their wingtip flares. The twinkling lights of a city provided landmarks; moonshine helped and bon fires, lighted by a devoted citizenry, were always welcomed. First of the nighttime pilots, Frank Yager, carrying Murray's mail, departed at 4:59 p.m., crossing the Great Plains to North Platte, Nebraska, in deepening dusk. For the last 70 miles of his trip, twilight folded into darkness, as the moon hid behind low hanging clouds. The veteran mail pilot pulled all 400 horses from the Liberty engine, racing the clock at a 100 mph. He flew low following the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and later the frozen North Platte River to his destination. At 7:48 p.m. Yager arrived at North Platte. Here began a flight that altered the course of aviation history, James "Jack" Knight's heroic flight through the night to save the airmail. Sporting a broken nose he had acquired three weeks earlier when his DH-4B mail plane crashed into a snow-covered peak in Wyoming's Laramie Mountains, Knight looked a sorry sight. Besides his aching nose, he was suffering residual effects from bruises and the concussion he'd acquired in the accident. As he admitted later, he didn't feel well enough to participate in the coast-to-coast airmail experiment, but he didn't want to be left out of the action; so he signed on. As soon as Knight spotted Yager's plane descending through the blackness of night into North Platte's airfield, he readied himself for the 248-mile relay to Omaha. Eager to get started, Knight was disappointed to discover that the engine on Yager's plane, the one he was scheduled to take to Omaha, failed to start. As a result he had to wait almost three hours, while mechanics repaired the plane's ignition. He paced the warm-up shack, smoked cigarettes and massaged his bandaged nose. Even at this point Knight must have felt fatigue. Unaware that he had been accepted for the cross-continent relay, the young pilot earlier that day had ferried a mail plane to Cheyenne and back. Finally, at 10:44 p.m., Knight roared down the runway before a large enthusiastic crowd. He began a steep ascent and disappeared into the night, climbing to an altitude of 2,200 feet.

Residents from five Nebraska towns along the route ignited bonfires in upended oil drums, which, like primitive beacons, spotlighted Knight's darkened corridor to Omaha. "Squinting down at them through drifting snow swirls, I felt as though many friends were sending me up signals of bon voyage," he said. At l:l0 a.m. on February 23, Knight let down at Omaha's Fort Crook, a former Calvary post. A large crowd had gathered at the well-lighted field, eager to catch a glimpse of this heroic Icarus of the night. Dead tired, hungry and stiff from the cold, Knight looked forward to a good meal and a warm bed. "This flying in the dark," he said, "takes it out of you." Knight anticipated turning his 16,000 letters over to either westbound relay pilot Hopson or Dean Smith. But, as he soon learned, the turnaround pilots scheduled to make the night flight from Omaha to Chicago and then back to Chicago were weather-bound in Chicago. And the only other available pilot who knew the route refused, because of the storm, to fly it. Knight volunteered his services, although he had never flown the 24-mile route from Omaha to Chicago via Iowa City before - even during the day. The weather looked terrible, snow flurries, winds and heavy clouds that blotted out the moon were forecast, and he was dead tired. But as airmail's options were fast running out, and nothing took precedence over the success of the airmail venture, Omaha's station manager, Bill Votaw, agreed to let the young pilot risk the flight. "I pleaded for the opportunity to go on," said Knight. "There's not a pilot in the airmail service who would not have done the same." For 20 minutes Knight pored over a road map of Iowa and Illinois, marking his course. Then he clambered into DH-4B number 188 - fueled and serviced - tucked himself into the cockpit, tacked his map to his instrument panel and opened the throttle. It was 1:59 a.m. His first destination was a refueling stop in Iowa City, 233 miles away. "I was flying over territory absolutely strange," he said. "I knew nothing of the land markings, even if they had been visible." To boot, his road map showed there was no main road that he could follow. Since Des Moines was the only city that stood out on the map, Knight set his compass course for that city 140 miles away, en route to Iowa City. This time no bonfires provided a primitive beacon for Knight to follow because everyone, except the tenacious young pilot, had given up. The night was as dark as pitch from a cloud-enshrouded moon, but Knight droned east over Iowa. An hour five minutes after takeoff he sighted the lighted dome of the state capitol, reassuring him he was on course. Twenty miles past Des Moines he encountered the forecast bad weather. Layers of clouds drifted beneath him, blocking his view of the earth. A strong wind whipped up from the northwest, beating his small plane like a tumbleweed in a storm. The turbulence caused him to increase throttle and thus burn precious fuel. To maintain visual contact and assess his drift, he nosed the craft down, descending as much as 2,000 feet. As he told it, when he felt his landing gear scrape the top of a tree, he pulled up. From then on he held the plane close to the ground even though the air was rough. The valleys were packed with fog and snow flurries pelted his windshield. Eventually, Knight sighted the railroad tracks leading to Iowa City. As much a threat as bad weather was sleepiness. To keep awake Knight gripped the control stick between his knees and slapped at his face, body and arms. The cold wind, which pricked like needles when he stuck his head over the side, jolted him into alertness. The cold air whistled under his helmet straps.

PHOTO: A de Havilland-4B wings its way coast to coast, bearing 350 pounds of mail. Wingtip landing lights were added to U.S. Air Mail Service planes once cross-country routes were established on a regular basis. Photo courtesy United Airlines. Finally, he sighted Iowa City, but with no lights to guide him he could not locate the airport. Thinking the project had been abandoned, the ground crew had all gone home. Knight circled the sleeping town for 12 minutes, hoping to rouse a sleeping field hand. Sure enough, upon hearing the drone of the distressed plane, the night watchman dashed out to the field and touched off several red flares. Provided with a general layout of the field, Knight made a nearly perfect landing. "...by more luck than skill," he said. When he landed, his gas tank was practically empty. The time was 4:45 a.m. The ground crew, now awakened, rushed to the field to service the plane. While the DH-4B was being gassed and serviced, Knight ate a ham sandwich, smoked cigarettes and waited to hear from Chicago that the weather was clearing. Although famished, he avoided eating too much, thinking it might induce more sleepiness. Finally, at 6:30 a.m. Knight revved his engine and took off for the Windy City. Even with the light from the awakening day, the exhausted pilot still flew nearly blind. A thick fog over the Mississippi lay like a white sheet over the land, forcing him to navigate by compass. He believed that by climbing to 5,000 feet he would find clear skies, and his instincts proved reliable. Clear skies over Illinois eventually allowed him to see identifiable landmarks on the outskirts of Chicago. As Knight swept over the city, his engine began to sputter and pop for the first time on the trip. "It was misbehaving, however, at a time when I was willing to forgive it," said Knight. "I was within gliding distance of the airmail field at Maywood." It was 8:40 a.m. when Knight set his wheels down on Chicago's Checkerboard Field. He described his flight from Omaha to Chicago to a New York Times reporter, "I got tangled up in the fog and snow a little bit. Once or twice I had to go down and mow some trees to find out where l was, but it did not amount to much, except for all that stretch between Des Moines and Iowa City. Say, if you ever want to worry your head, just try to find Iowa City on a dark night with a good snow and fog hanging around. Finding Chicago - why, that was a cinch. I could see it a hundred miles away by the smoke and by the stockyard smell. But Iowa City - well, that was tough." Knight had winged his way into aviation history, completing 672 miles of night-flying, the first all-night mail flight. He'd also set a record when his mail from San Francisco was delivered to Chicago in 29 hours. Otto Praeger spared no praise for the all-night flight, calling it "a demonstration of the entire feasibility of commercial night flying." Only a few photographers greeted the young pilot, however. After all, they figured, what fool would fly through a night like this. Even though the worst was over, that didn't mean smooth flying lay ahead for the two relay pilots trusted with the experiment's critical final laps to New York. Within 20 minutes of Knight's landing, newly employed mail pilot Jack Webster took wing, bound for Cleveland. A low ceiling had him skimming trees tops and nearly force-landing his plane, but he stayed aloft. Even though he had never flown the route before and never had seen the Cleveland field, Webster delivered his mail pouches safely to Allison for the last leg of the trip. Carrying six mail bags of transcontinental mail, Allison took off from Cleveland in DH-4B number 192, the same craft that vibrated the ice off his wings and wires and saved him from a cold winter's dunking in the Allegheny River the day before. This time the propeller spun like a top, but the weather posed as much a threat as ever. Allison encountered snow and sleet across Ohio but persevered, landing at Bellefonte for gas and oil at 2:42 p.m. Sixteen minutes later he continued his assault on the Allegheny "Hell Stretch" and its hair-raising obstacle course. At 4:50 p.m. on February 23, Allison dipped his wings at Hazelhurst Field in New York, five minutes ahead of schedule, thus concluding the historic event. Praeger hailed the achievement as "the most momentous step in civil aviation" and prophesied it would revolutionize the carrying of mail worldwide. Newspapers touted the coast to-coast flight as a feat without parallel in civil aviation. The big airmail gamble had paid off. For the first time in history, mail had been carried the 2,666 miles coast to coast in 25 hours, 53 minutes flying time at an average speed of 103 mph. Elapsed time from the time Nutter took off from San Francisco until Allison landed at New York was 33 hours 20 minutes, 75 hours shorter than the best train time. Impressed by the feat and by the wide public acclaim, Congress at last appropriated the needed funds for the beleaguered mail service. The U.S. Air Mail Service and the first cross-country transcontinental experiment have long since faded into history. But because of the daring flight, the service's role in pioneering air transportation remains as a milestone in world aviation. The tragedy of pilot Lewis, the triumph of Knight and the courage and perseverance of Allison and the other mail pilots brought aviation to this glory point. "We realized if we could make it go, it could amount to something," said Allison. Nancy Allison Wright is editor of the Air Mail Pioneers News, a periodic newsletter of Air Mail Pioneers. Her father, Ernest M. "Allie" Allison, was former national treasurer and western division president of Air Mail Pioneers. |

History |

Air Mail Pilots

|

Photo

Gallery |

Flight Info

|

Antique Airplanes

|

Members |

|

copyright © 1999 Nancy Allison Wright, President Air Mail Pioneers

|

When

he taxied up to the hangar, he was met by incredulous field hands,

surprised at seeing him. They had expected Allison to meet the same

fate as Leonhardt. Seven minutes after Allison landed in Cleveland,

relay pilot Wesley L. Smith took to the air, bearing Allison's load

of mail, headed for Chicago. He endured a turbulent ride through

a raging storm but landed safely at Checkerboard Field, Maywood

(Chicago), where he passed his mail to pilot William C. Hopson -

who was also a daring wing-walker. Ten minutes after flying in heavy

snowfall Hopson returned to the field, saying that there was no

way he could battle this storm. Snow, rain and fog at both Chicago

and the refueling stop, lowa City, had scratched the westward flight.

When

he taxied up to the hangar, he was met by incredulous field hands,

surprised at seeing him. They had expected Allison to meet the same

fate as Leonhardt. Seven minutes after Allison landed in Cleveland,

relay pilot Wesley L. Smith took to the air, bearing Allison's load

of mail, headed for Chicago. He endured a turbulent ride through

a raging storm but landed safely at Checkerboard Field, Maywood

(Chicago), where he passed his mail to pilot William C. Hopson -

who was also a daring wing-walker. Ten minutes after flying in heavy

snowfall Hopson returned to the field, saying that there was no

way he could battle this storm. Snow, rain and fog at both Chicago

and the refueling stop, lowa City, had scratched the westward flight.

"I

dared climb no higher, because land markings were barely discernable

at this level," he said. Clouds obscured the moon, but flying through

the scud bothered him little, as he knew the route well by day.

Through rare holes in the cloud cover, he recognized cities and

towns along the way from their light patterns and caught glimpses

of the dim silver thread of the Platte River.

"I

dared climb no higher, because land markings were barely discernable

at this level," he said. Clouds obscured the moon, but flying through

the scud bothered him little, as he knew the route well by day.

Through rare holes in the cloud cover, he recognized cities and

towns along the way from their light patterns and caught glimpses

of the dim silver thread of the Platte River.