|

|

|

A LIFE IN

AVIATION: Stanhope S. Boggs

|

|

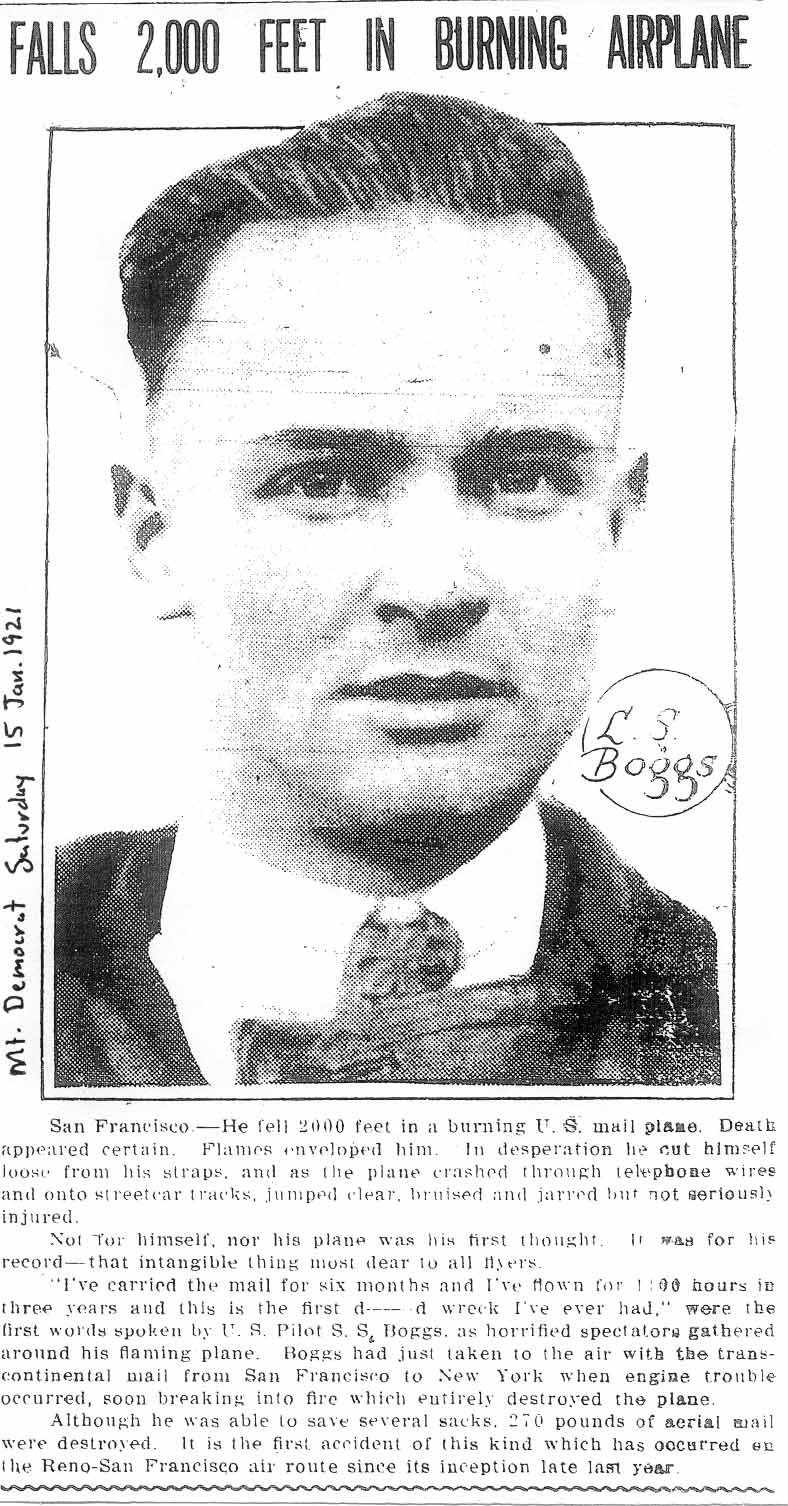

When Stanhope Stewart Boggs joined the U.S. Air Mail Service on August 2, 1920, he hardly realized he d signed on for a job fraught with terror, but one morning five months later, flying out of San Francisco bound for Reno, the realization became abundantly clear. Boggs knew that the newly formed Post Office airmail enterprise suffered an inordinate number of tragedies.

Up to that time, eight pilots, two mechanics, one clerk and a division superintendent had died in crashes, much of it due to faulty equipment. As a flight instructor at San Antonio s Brooks Field from 1918 to 1919, Boggs had all ready experienced such dangers. Still, at age 25, discharged from military service with a record 1,100 hours in the air without an accident, he felt confident that a bright future lay ahead for him in the new field of aviation. Came the morning of January 4, 1921; fog cloaked San Francisco like a blanket, causing his plane, as well as others lined up at Marina Field, to drip water. At 7:00 a.m., the field supervisor advised him to take off; daylight was just breaking. Did Boggs climb into the cockpit of his DH-4, thinking he d prefer to wait until the white mist lifted? Perhaps, he thought he could cut through the pea soup and reach clear skies in open country over the Sierras. He adjusted his goggles and yelled, "contact" to the field hands who pulled the prop through to compression. At 7:10 he ascended into the murky sky. The converted WWI fighter, loaded with 470 pounds of first class mail, rose in long easy circles to a height of 2,000 feet. He craned his neck to look at the city below, its lights barely visible.

While 100s watched, horrified, the plane plunged through the air; with a roar heard for blocks, it crashed into the wires, then struck the pavement, burst into flames that shot high as the telephone polls. Boggs jumped out of the burning plane, virtually uninjured and scrambled to a nearby fire alarm box to alert the fire department. Pedestrians, street cars and automobiles barely escaped injury, though one street car screeched to a stop a few feet from the plane when it lost power from the broken wires. Boggs attributed the accident to the moisture from the fog, which had collected in the carburetor and leaked into the fee jet. As the plane struck an air-bump, the engine stopped dead. Not one to let an accident interfere with his plans for an aviation career, Boggs continued flying for the Air Mail Service.

By the time the Post Office contracted airmail to private carriers in 1927, Boggs had put in six years. For the next thirty-nine years he worked for the FAA, traveling across the United States locating possible airport sites. He became an active member of the Air Mail Pioneers.

In 1929 he married Margaret Mills. The couple lived in Santa

Monica, California, where they raised their son, Marshall Stanhope

Boggs, born in 1935 and died in 1976. Grandsons Randall Marshall

Boggs and Craig Steven Boggs carry on the family name.

|

History |

Air Mail Pilots

|

Photo

Gallery |

Flight Info

|

Antique Airplanes

|

Members |

|

copyright © 1999 Nancy Allison Wright, President Air Mail Pioneers

|