|

|

NEWSLETTERS -- WINTER 2001

|

AUTOGRAPH BONANZA Thanks to Ann Marshall, daughter-in-law of Tex and Katherine Marshall, the AMP memorabilia collection includes a bevy of signatures from AMP reunions. Tex and Katherine Marshall valued their friends in AMP so much they asked them to autograph a new white Cannon percale cloth, in remembrance of good times together. The result is nearly 100 autographs of AMP members who long ago took their Last Flights. Imagine the scene: It is the National AMP reunion. The date is October 12 to 13, 1956; the place, the Oak Park Arms, Chicago. The sound of conversation fills the hall as AMPs gather for the gala event. They greet old friends and mourn the passing of those who took their Last Flight. In the Patio Room, the Marshalls whip out the cloth; they lay it on a table, just the right length to accommodate its banquet-size spread. Tex furnishes the pens, green indelible ink. As national president, Tex signs one end; Katherine in her neat hand inscribes her name on the other. Clarence K Stewart, national AMP secretary is present, as are Arlene and Raymond Lange, Bill Sears, Eleanor Morgan, Ed and Irene Keogh, Paul Collins, Phil Coupland, to name a few of the more than 50 in attendance. One member pens his name with a flourish, characteristic of a Coney Island portrait artist. Thomas J. Meyer draws himself in profile. He adds the words "Stevenson for President and Egghead and I." He also says, "Hi thrs Tex, I Dood it." Next he fashions an oak leaf with the inscription Vi de Marco. Meyer also draws a profile of Clifton P. "Ole" Oleson, sporting a pair of eye glasses. The dates 1913 - 1956 may signify that Ole died the year of the reunion. Edward A. Keogh leaves a message for the Marshalls: "Remember the dinner without tartar sauce. Ole knows how to make but not Duncan Hines."

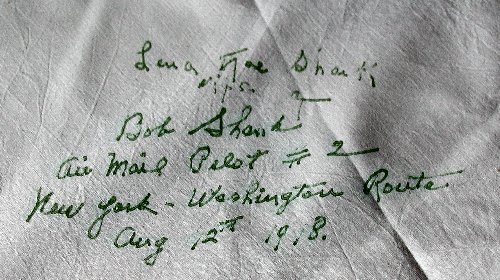

Royalty is present in the person of Bob Shank, Air Mail pilot #2, New York Washington, 8/12/18. Now imagine another scene. Four years have passed. It is 1962. The Marshalls depart for the Las Vegas reunion. the signature cloth carefully tucked in their suitcase. This time members sign their names in blue indelible ink. Many added their addresses, as well as the ubiquitous comments. "I chased the DH4 that day on Sat Lake," noted Lennie Jones, also signing for his wife Jessie. Among those in attendance are Mary and Harry Huking, Ernest and Florence Allison, Burr Winslow, "Uncle" Luke Harris, George and Charlotte Pomeroy. By the end of the reunion Katherine and Tex have garnered over 100 signatures. They fold the precious cloth, return it to the suitcase and bring it home. A job well done, they congratulate each other on securing a treasure of indelible memories from good friends. |

|

AIR MAIL

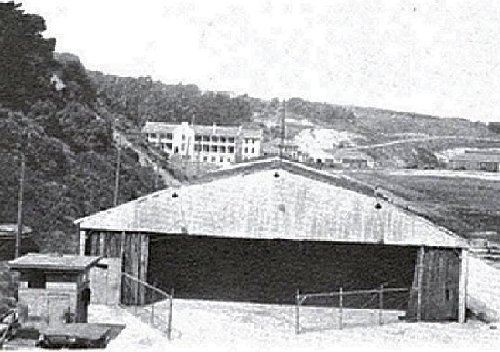

HANGAR SURVIVES BULLDOZER Try locating an genuine U.S. Air Mail Service hangar anywhere along the old transcontinental route, and you ll meet disappointment at every turn. You ll discover that material signs of aviation s golden age have gone the way of the dodo bird and the passenger pigeon; sadly replaced by shopping centers, strip malls and parking lots. Only last year -- as reported in AMP News spring 2000 -- the Bryan, Ohio airmail hangar was reduced to rubble. A shortsighted owner could see no reason to retain the historic structure. Yet one hangar has survived the onslaught the airmail hangar at Crissy Field in San Francisco. It stands perched but empty at its original site, the extreme east end of Crissy Field in San Francisco s Presidio. Beautifully located, it looks across the bay to the Golden Gate Bridge.

When the Post Office scouted for a suitable landing field in San Francisco, none presented better possibilities than the Army Air Service airport, then called the Flying Field at the Presidio. Major Henry "Hap" Arnold led the successful effort to change the name to Crissy Field in honor of Major Dana H. Crissy, who crashed and died in October 1919 in a de Havilland 4-B during an Air Service transcontinental reliability test. Under the auspices of the Air Mail Service, San Francisco and Crissy Field gained fame as the site of many early aviation milestones. On September 11, 1920, airmail pilot Edison Mouton, flying the final leg of the first transcontinental run, landed at San Francisco s Marino Field. (One year later the Post Office moved from Marino Field to the Army s Crissy Field.) The date was September 11, at 2:20 p.m. The actual flying time for the bold experiment, 34 hours and 5 minutes, elapsed time 75 hours and 52 minutes. Upon landing, Mouton was greeted by eager dignitaries and a bevy of flashing camera bulbs. Anticipation gripped San Francisco and the nation on February 21, 1921, the day of the experimental first day/night transcontinental. At 4:30 a.m. two planes departed from New York and two from Crissy Field, piloted by Farr Nutter and Ray Little. Two and one half hours later, after crossing the 18,000-foot Sierra Nevada range, Nutter and Little landed in Reno. Their successful effort, in combination with that of the other east and westbound pilots, launched Air Mail. Crissy Field played a major role in trial night flying. On August 21, 1923, the first day of the four-day demonstration of the transcontinental service, airmail pilot Clare K. Vance completed the west-bound flight, landing at Crissy Field at 6:24 p.m. In 1928, after the Post Office contracted airmail routes to private carriers, Crissy Field was turned into a barracks for ROTC students. By 1941 it had been transformed into the Army s intelligence language school for training Japanese/American interpreters. Today, the school s former students honor the site as a historical monument. A plaque commemorates the Japanese/American contribution to WWII as America s first class of interpreters. An outgrowth of the language school is the Defense Language Institute, located in Monterrey, CA, In 1994 Crissy Field came under supervision of the National Park Service. Its fate now rests in the hands of the Presidio Trust. Aviation history buffs and journalists who troop to the site will see no acknowledgment of the hangar s humble origins. No sign at its entrance indicates that it was once used to house U.S. Air Mail Service aircraft. This is not the case for other Crissy Field buildings. The Crissy Field Aviation Museum Association has undertaken an extensive restoration/preservation project to preserve, what they call, "the long and rich history of aviation at Crissy Field." They plan to turn the Park Service site into a waterfront showpiece, featuring a museum, offices, gift shop, extensive grass area, picnic facilities and large parking lot. The DH-4 that Major Crissy was flying when he crashed is now being reconstructed and will highlight the new exhibition site. NEWS FLASH Your editor conferred by phone yesterday with a well-known San Francisco architect named Gerald Takano. He heads an organization whose goal is to renovate and preserve the Crissy hangar. You may wonder why. Takano and his group want to turn the building into an interpretive center, complete with photos and text, honoring its ultimate occupant the Japanese/American language school. He was unaware of the building s origin as an U. S. Air Mail Service hangar. After I told him why the building was built in the first place, he enthusiastically proposed that AMP join his lobbying and fund-raising efforts. In your editor s opinion, Crissy Field offers a rare opportunity to create a physical memorial to the Air Mail Service. I accepted his offer with pleasure. As the plan stands, once we secure rights to the property, photographs and text will trace the building s history from its Air Mail days to its WWII Army past and finally its use as the Japanese/American school. Takano submitted a formal proposal but doesn t expect to hear from the Presidio Trust until late in the summer. |

History |

Air Mail Pilots

|

Photo

Gallery |

Flight Info

|

Antique Airplanes

|

Members |

|

copyright © 1999 Nancy Allison Wright, President Air Mail Pioneers

|