|

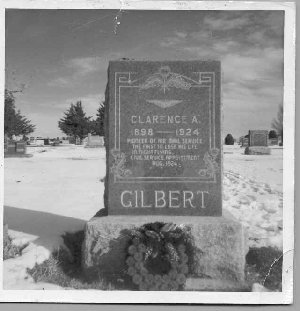

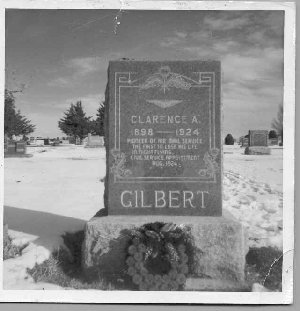

Clarence A. Gilbert

First tragedy of night/day transcontinental airmail

Clarence A. Gilbert join ed

the U.S. Air Mail Service committed to a vision of air travel's

glorious future. In a note penned to his family he wrote

that airplanes "backed the automobile off the map." With

characteristic enthusiasm, he entered de Havilland training,

ready, as he said "to give her the gun." ed

the U.S. Air Mail Service committed to a vision of air travel's

glorious future. In a note penned to his family he wrote

that airplanes "backed the automobile off the map." With

characteristic enthusiasm, he entered de Havilland training,

ready, as he said "to give her the gun."

Gilbert gave the WWI

English-built bomber de Havilland "the gun" first as a U.S.

Army flying cadet and later as a flying sergeant at Ft. Crook,

Omaha. An accomplished pilot, the Army 2nd lieutenant

was easily accepted into the Air Mail Service on August 15,

1924. After briefly serving as a mechanic and relief pilot

at Iowa City, he received a regular appointment, flying the

mail from Chicago to Iowa City.

Came the night of December 21, 1924;

Christmas mails were accumulating and additional flights

deemed essential. Gilbert was pressed into service.

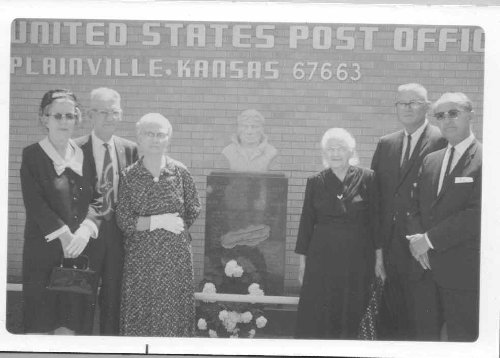

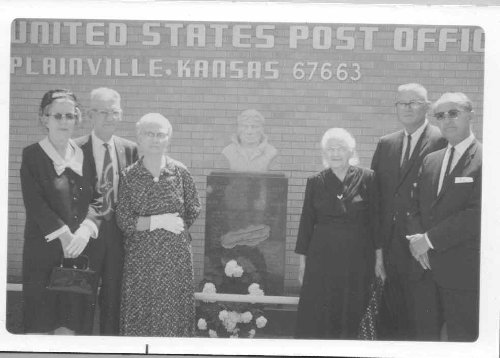

Many years later Congressman Bob Dole,

principal speaker at a dedication ceremony to Gilbert in his

home town, Plainville, Kansas, described the day of the tragedy.

"December 21, 1924, was a drab winter day with a low, gray overcast,"

he began.

"The horizon was only dimly outlined, and visibility was cut

to a few miles by a blue haze. This last-minute Christmas

rush was on, both in the store and in the air mal; and extra

sections were called in to help transport the surplus packages.

Clarence Gilbert was one of two pilots chosen to fly the mail

west that day.

"The horizon was only dimly outlined, and visibility was cut

to a few miles by a blue haze. This last-minute Christmas

rush was on, both in the store and in the air mal; and extra

sections were called in to help transport the surplus packages.

Clarence Gilbert was one of two pilots chosen to fly the mail

west that day.

"He took off from Chicago

on scheduled time [7:00 p.m.]; and as he flew west, he encountered

a blinding snow storm which obscured the very essential flares

of the lighted airways below. It is assumed that Clarence

Gilbert, unable to rely on his sense of direction, balance,

or altitude, finally decided to relinquish the plane to the

unyielding elements, and if possible, save his own life.

He paused long enough to cut the ignition, thus preventing fire

and saving the mail.

"He then stepped over the

side, but his parachute had opened too close to the plane and

the tail surfaces cut the lines, rendering his parachute useless.

His resulting death was the first fatality since night flying

had begun in July of that year.

"Much credit should go to

those intrepid aviators who from May 1918, onward fought the

battle of flying the mails. These pilots were true adventurers.

They returned to the jobs day after day, coolly weighing their

chances. In a time when most men plodded from home to

office and office to home, this small group was set apart by

an occupation wherein each departure bore the chance they may

not return.

"Clarence Gilbert was in

every sense of the word a 'pioneer' and a 'hero.' It is

both fitting and proper that we pause to dedicate this memorial

to him today."

Photo Gallery

Left: Clarence Gilbert on

left. Right: Clarence and Blanche Gilbert in 1923

Clarence Gilbert in de Havilland

Back Row Left to Right: James

Gilbert and Harlan Gilbert (brothers). Front Row: Blanch

Murphy (widow), Ethel Shepherd (sister), Rose Gilbert (mother),

Ed Murphy.

All photos courtesy of Anita

Wilson

Killed in snowstorm

|

ed

the U.S. Air Mail Service committed to a vision of air travel's

glorious future. In a note penned to his family he wrote

that airplanes "backed the automobile off the map." With

characteristic enthusiasm, he entered de Havilland training,

ready, as he said "to give her the gun."

ed

the U.S. Air Mail Service committed to a vision of air travel's

glorious future. In a note penned to his family he wrote

that airplanes "backed the automobile off the map." With

characteristic enthusiasm, he entered de Havilland training,

ready, as he said "to give her the gun." "The horizon was only dimly outlined, and visibility was cut

to a few miles by a blue haze. This last-minute Christmas

rush was on, both in the store and in the air mal; and extra

sections were called in to help transport the surplus packages.

Clarence Gilbert was one of two pilots chosen to fly the mail

west that day.

"The horizon was only dimly outlined, and visibility was cut

to a few miles by a blue haze. This last-minute Christmas

rush was on, both in the store and in the air mal; and extra

sections were called in to help transport the surplus packages.

Clarence Gilbert was one of two pilots chosen to fly the mail

west that day.