Art Smith wasn't shy. Wasn't shy or backward about anything, especially his dream. Art Smith wanted to fly. He'd read and heard about the Wright brothers, and although he didn't know a thing about flying, he knew he could learn. True, he had no plane, no friend with a plane, no benefactor-had never even seen a flying machine, in fact-but still his dream spurred him on.

Arthur Roy Smith, February 12, 1926 |

One summer at Lake James in Steuben County, while sitting in a boat with his fourteen-year-old girlfriend-to-be, Aimee Cour, Art watched a big turkey buzzard circle lazily in the sky. He was fascinated by the way the buzzard soared on wind currents without moving its wings, and he wondered how it could be that a heavier-than-air machine could stay off the ground. "I thought about the buzzard's wings and aeroplanes, and wondered if the same principle kept them in the air, and what it was," he later wrote. Determined to figure it out, Art announced to Aimee, "I'm going to make a machine and fly in it."

The year was 1909, and it had been only six and a half years since Orville and Wilbur Wright had first flown their machine. American aviation-mostly a matter of experimentation by single individuals in backyard sheds and barns-was just beginning. No one knew about airports, control towers, or radar. There was no such service as air mail.

When Art returned to his home in Fort Wayne from the camping vacation at Lake James, he collected all the books and magazine articles on aeronautics that he could find. Few were available, but one that was helpful was Vehicles of the Air by Victor Lougheed. From the resources he could gather, Art learned about aircraft construction, designs, and patents. At night, he'd pore over his books and study how to build a flying machine. He believed he could build a plane that would fly better than the Wright brothers' airplane, and as he worked on his design, he was careful to avoid infringing on their patents.

Adding to Art's determination was his father's deteriorating eyesight. His father, James F. Smith, was a carpenter-contractor, and in the evenings, as Art helped his father figure contracts, he became increasingly aware that his father was having trouble seeing. His father had worked hard for seventeen years to get his carpentry business going, and now just as it was beginning to flourish, he was having to turn down work because of his eyesight. Art was determined to help his father any way he could. "He was a slow, quiet man, with a kind of silent strength," Art said of his father. "He never spoke of it, but he fought the idea of blindness terribly."

In magazines, Art had read about various flying competitions, especially the Scientific American prize, the Schebler prize, and other contests. Art believed if he could build a plane, he would then be able to fly in aviation competitions and win some of the prize money. Even the smallest of all the prizes would be enough to pay for treatment that would save his father's eyesight.

At night, Art plotted his ideas. He built models of airplanes using sticks and rubber bands. He was sure he could come up with an airworthy machine because he had an idea about using a large stabilizer for his plane that would not only make his airplane fly better than others but would make him famous as well. He planned to get his invention patented.

One night Art screwed up his courage and talked to his father about his dream, telling him about the Wright brothers and reading him some magazine articles. While Art was reading, his mother came into the room. His father turned to his mother and said, "Art wants to be an aviator." His mother was appalled. She voiced concerned about the dangers of flying. Art answered her questions as well as he could and went on to explain that in order to fly, he would have to build a plane. Art's father asked him how much it would cost to build the plane. Art didn't know exactly, so he calculated a budget and presented it to his parents a week later. He figured he would need $1,756.60 for materials-that is, if he did the work himself. Perhaps it was Art's earnestness, or maybe it was his father's realization that his options were few, but several days later at the supper table, the Smiths announced that they had taken out a bank loan for $1,800.00 using their house as collateral.

With his parents' financial backing, twenty-year-old Art quit his job and devoted himself to pursuing his dream. That summer and fall, Art and a "chum," Al Wertman, worked frantically to build a machine that would fly. Al liked challenges, and Art was bold and inventive. Al was a mechanic, carpenter, and a craftsman, and he complemented Art's skills. Together the boys made a good team.

In order to keep secret the stabilizer that Art had designed, the boys kept the windows of Art's workshop covered. They worked all day and late into the night, occasionally stopping to show off their work to a few neighborhood friends. One friend, Paul Hobrock, wrote that on Saturday mornings, he used to visit a friend "who lived on the Bass Road close to Art Smith and his folks. Since Art was building an aeroplane, we naturally went to his house to see what was going on. . . . Art was glad to have us do little chores such as sand-papering struts and other wooden members."

Instead of the projected six weeks, it took Art and Al almost six months to construct and test their airplane. Unsure of what they were doing, Art and Al experimented; at night Art studied his books. Time and money soon ran short. With the bank loan due date pending, it was imperative to get the contraption off the ground for testing. The boys finished on 17 January 1910 with only twenty-three dollars left in Art's account. The new machine was a Curtiss-type biplane with a forty-horsepower Elbridge engine. The undercarriage consisted of two wheels in tandem and wing skids near the tips of the under panels.

The night they finished the plane, Art and Al moved it through the streets of Fort Wayne to a field in what is now Memorial Park. The next morning, 18 January 1910, with only his parents, Aimee, Al, and another friend present, Art tested the flying machine. The plane reached almost fifty miles per hour before leaving the ground. Suddenly it rose alarmingly, dipped, rose again, and crashed into the ground. Art was thrown onto the frozen ground. He was badly injured, and the plane was ruined except for the engine.

According to popular accounts, Art spent the next six months lying in bed, although in his autobiography Art says he lay in bed, recovering, for five weeks. In any case, while recuperating from his badly wrenched back, Art thought through all the theories he knew and analyzed the problems he had had with his machine. He decided the oversized stabilizer had been too sensitive. He also decided there was nothing else to be done except to build another plane.

With very little money available for supplies and the mortgage due in less than five months, Art tackled the job with tenacity. Only a few of the original supplies could be used to serve as the nucleus of his second plane. The Smiths went to the bank and asked for a renewal of their mortgage, but the bank refused, and in due time, the Smiths lost their house. The Smiths then traded the equity they had in the home for two small parcels of land. The parcels did not include a house, but Art and his father were permitted to live in the barn while they worked on the plane. Art's mother went to Berne to "visit" her cousin Annie.

According to several accounts, at this time Aimee Cour's father ordered her to sever her relationship with Art. Like most people, he thought Art was a dreamer, and certainly Art did not hold a good job.

During this desperate time, Al Wertman quit his job at a cigar company in Auburn so he could help rebuild the plane. Al even invested his life's savings of fifty dollars in the project. Art never forgot Al's generosity and later wrote, "I care for him today as deeply as I do for anyone on earth. Every ounce of manly affection I can feel belongs to Al Wertman, for the splendid, unselfish service he gave me in those days."

During the summer of 1911 the boys continued working on their plane. Repeated test flights taught Art more about his machine. Art and Al worked feverishly, trying to test everything they could think of, but everything seemed to go wrong. By now many people knew about Art's plane and ridiculed him. Some called him crazy, but Art didn't care. He was determined to become an aviator, no matter how long it took. He did have his doubts, however, when a team of exhibition fliers from the famed Curtiss Flying School came to Fort Wayne that summer. When they heard about Art's plane, one of the fliers asked to see it. After he inspected it, he told Art there was no way the plane would fly. Art was stung. Years later he remarked, "At times, it got rather discouraging."

Desperate for funds, Art and Al decided that if they were to exhibit their plane, maybe people would pay to see a flying machine. They guessed right. Since most people never had seen a plane, they were more than willing to pay to see even an unfinished one. Art displayed his machine at Fort Wayne's old Driving Park, and 155 people paid ten cents each to view-and laugh at-his efforts.

Knowing they needed more formal aviation training, Art and Al took the $15.50 they collected from exhibiting their airplane and hopped a boxcar to Chicago. They sought out the Chicago School of Aviation. They were shocked to learn that tuition cost $350.00. The boys could do nothing except study the planes parked at Hawthorne Race Track and Cicero Field. They spent three weeks doing just that then hopped a boxcar home.

Although they had budgeted their money well, Art and Al needed more for supplies to finish the plane. Again James Smith went to the bank, and by offering his two lots as collateral, he talked bank officials into lending him an additional two hundred dollars. Art knew the only way to get sponsors to invest in his machine was to succeed, and now with another mortgage date looming, he was nearly frantic but ever more determined. He also wanted to fly for a Scientific American competition that would underwrite all his expenses.

Finally, on 10 October 1910, Art was ready to fly his second plane. This time, however, the boys were more savvy. They decided to advertise the flight as an exhibition. Art announced he would attempt to fly from Fort Wayne to the nearby town of New Haven, and crowds of spectators, including newspaper reporters, turned out to watch.

With a kitten named Punk along for the ride, Art took off and headed east toward New Haven. The plane rose to five hundred feet, and then suddenly there was silence. The engine had stopped. With skill and pluck, Art managed to glide down into a field. He discovered that a broken line from the radiator had drenched both the engine and the kitten. A young boy was dispatched to buy some solder, and soon Art was back in the air. When he returned to Fort Wayne, he enjoyed tumultuous applause.

Art still needed money to pay back the mortgage, so he decided to schedule exhibitions in Fort Wayne on Saturday and Sunday, 21 and 22 October. Publicity was wonderful. "He's just a fool kid with a crazy notion," people said, but they were excited. A large crowd showed up Saturday, ready for a fantastic exhibition, but the wind was choppy. Although he was wary, Art went up twice anyway. The plane stayed up only minutes each time, but it was long enough to shock the crowd that had turned out to watch the "Smash-Up Kid." The spectators went wild. Suddenly Art was a hero; people referred to him as Fort Wayne's "Bird Boy."

Poor weather on Sunday forced Art to cancel that day's exhibition, but he rescheduled it for a week later. On Sunday, 29 October, the weather was again marginal, but Art was determined to fly because several hundred fans were waiting. The flight was short and perilous, and it culminated in a death dive. At the last moment, Art gained control of the plane and landed two hundred feet downfield. The crowd cheered, and his mother fainted. Art collected nearly $300.00 from the audience, bringing total receipts from the two late-October exhibitions to $589.50. With this money, the young men were triumphant; Art had enough to pay off the loan.

Art had told his parents he'd pay back every dime as soon as he could, and the next morning, Art and his father walked into the bank. Art said, "I felt like playing leap-frog over that solemn banker's own desk."

About a week later, a man from Mills Aviators of Chicago came by the house while Art and his parents were eating breakfast and asked him to consider giving some flying exhibitions. "He was a fat, well-dressed man, with a diamond in his tie, and diamond rings," Art wrote. "He said he had bookings for Bay City and Bryan, Texas, which I could fill immediately, and that he would give me a year's contract with Mills Aviators which would make me thousands of dollars. The two flights already arranged should make me at least $2,500." Art signed. He now had a contract for what seemed like a fortune. He promised Aimee he would buy her an engagement ring.

Art went to see Mr. and Mrs. Cour. Later, he wrote, "Mr. Cour was very pleasant to me that day. He spoke about my flights and said he was glad to see I had succeeded with them. Then he began to talk about the dangers of aviation and how precarious it is. . . . He urged me to give it up and do something else." But Art couldn't give up the idea of flying. He decided he had to succeed. With a big bank account, he believed the Cours would treat him differently.

Art excitedly headed for Texas, only to encounter disappointment. Because of a strong wind, his flight in Bay City lasted only two minutes. The landing was rough and the plane was damaged, and the remaining scheduled flights were canceled because of incessant rain. Art made $350. In Bryan, the young aviator encountered disaster. When he was approximately 250 feet off the ground, he struck a heavy downward current of air and sank. His plane crashed in a belly flop, and everything except the engine was reduced to splinters. The crowd jeered. A few boys begged Art for the splinters and bits of canvas. Remembering his own dream of flying, Art gave them whatever they wanted and shipped his engine back to Fort Wayne. He barely had money for his fare home.

No one would give Art a loan even though his father offered to mortgage his lots a second time. Investors were skeptical. Again to them Art was nothing more than the "Smash-Up Kid." Aimee told Art her father would not allow her to marry him.

Meanwhile, Art heard about Steve Fleming, a wealthy Fort Wayne politician who raced automobiles. As a last resort, and although he didn't really expect to receive any help, Art decided to ask Fleming for financial backing. He offered his father's lots as collateral. Again, Art's enthusiasm was contagious. Fleming gave him a long-term loan. Mills Aviators let Art use their plant to construct a new plane and helped him in the process. They booked an exhibition flight for him in Sterling, Illinois. It was the beginning of a new chapter in Art's life.

In Sterling, a strong air current flipped the plane over, and Art had to repair it. The plane crashed again in Mattoon, Illinois. Art decided he needed a stronger engine that would not leave him to the mercy of the winds, but before he could get one, he had to give an exhibition on 29 June 1911 in Muncie. Art was excited; on his way back to Indiana he would be able to see Aimee and visit with his friends. He couldn't have anticipated the excitement he would face in Muncie.

When he saw the Muncie landing area, he was shocked. It was full of trees and inadequate for any sort of takeoff, especially in a strong wind. He agreed to display the plane but refused to fly. Unfortunately, the spectators demanded a flight. They began to throw bottles and bricks. When Art realized the crowd was going to destroy his plane, he jumped in, turned on the engine, barely avoided some trees, and escaped. He landed in a nearby meadow where he plowed head-on into a fence. The managers gave him fifty dollars of the receipts, but the plane was a wreck.

Art had the machine fixed in time to exhibit it five days later at a Beresford, South Dakota, Independence Day show. That demonstration was more successful than recent ones had been, and Art earned $750. The first thing he did with his prize money was to take his father to see "the finest oculist in Chicago." Unfortunately, he was told that nothing could be done to save his father's eyesight.

As the summer of 1912 progressed, Art's fame spread. Circuses and fairs throughout the Midwest inquired about featuring him in flying exhibitions. Some agreed to pay by the show, others by the number of minutes the machine was airborne. Art gave demonstrations in Elkhart, Indiana; Hillsdale and Adrian, Michigan; and Deadwood, South Dakota; as well as in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, Minnesota, and West Virginia.

From his many flying exhibitions, Art began making money. It wasn't long before he bought Aimee an engagement ring. Aimee's father, however, was still not willing to accept Art's line of work. After a fantastic exhibition in Fort Wayne in which Art took Aimee for a ride without asking permission from her father, Mr. Cour was so upset he told Art, "You can't marry Aimee now; that's final. Get into some other work, and come back in three years, and I may think about it."

A week later, Art and Aimee eloped. It was reportedly the first aerial elopement in history.

The day of the elopement, 26 October 1912, was warm. Art and Aimee took off in Art's plane for Hillsdale, Michigan, where they planned to be married; after six minutes in the air, however, the engine began to skip and the couple had to make an emergency landing. One of the valves was broken. Art telephoned his mechanic and his friend Al Wertman and asked them for help. With their assistance, the plane was soon fixed, and the couple was on its way once more.

Outside of Hillsdale, the plane again malfunctioned, and this time it crashed into a field. A man delivering a mattress for a furniture store was the first to see the wreck. He came over, put Art and Aimee onto the mattress, and took them to a hotel. "They thought we were dead," Art later said. At the hotel, Art and Aimee lay unconscious in separate rooms. When they came to, they insisted on being together. Someone got a minister. Bandaged and racked by pain, the two were married lying side by side. By the time Mr. and Mrs. Cour arrived, they were so thankful Aimee was alive, they forgave the couple. It was weeks before the two were well and Art off his crutches.

The next years were busy ones. Exhibition flying took the young pilot to Oklahoma, where he inspired young Wiley Post to a life of aviation, and back to Texas, where he became associated with Lincoln Beachey. He and Aimee traveled together throughout the country, often driving a runabout, shipping the disassembled plane by train. During this time Art began "fancy flying" and performed stunts such as loops and dives. For the first time, Art felt free from financial worries. He bought his parents a comfortable home and gifts for Aimee.

Art Smith's life dramatically changed in 1915. Lincoln Beachey, who was preparing to fly in the San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition, was killed in a flight that year, and Art asked to replace him. His request was granted, and the next four months were wonderful, not only for Art but also for the exposition. Art's aerobatics, including loops, "death spirals," and night flights using phosphorus fireworks, captivated the crowds, and he became an immediate celebrity. The San Francisco Bulletin serialized and published his story, and a souvenir booklet was a near sell-out. Meanwhile, the Oakland Enquirer caught the pièce de résistance on film: Art Smith flying his plane at night over the blazing lights of the exposition.

Art's fame spread around the globe. In the spring of 1916 he was offered ten thousand dollars by the Japanese for a series of exhibitions. As in San Francisco, his shows dazzled the crowds. Fascinated spectators included the Crown Prince and his brothers. Art also delighted Prince Kuni, president of the Aero Society, by explaining the details and workings of his machines. Art was the toast of Japan and entertained by dignitaries and royalty. One newspaper reported, "The most distinguished body of men that has ever gathered to do honor to an aviator in this country attended the banquet given in honor of Art Smith, the American birdman, at the Imperial Hotel last night." Guests at the banquet included Dr. Okuda, the mayor of Tokyo; Baron Shibusawa, a prominent industrialist; General Nagaoka, president of the National Aviation Association; professors from the Imperial University; and "some of the greatest men of an Empire."

Although Art's Japanese tour was scheduled to last four months, a landing accident in Sapporo brought it to an abrupt end. Art suffered a broken leg, and his plane was badly damaged. Art returned to the United States but promised to go back to Japan the following year to fulfill his contracts.

Perhaps because of the difficulties of being a celebrity or the constant traveling, Art separated from Aimee. Newspaper articles speculated about the reason: Aimee reportedly accused Art of becoming a "swell-head," and Art accused Aimee of having "kissed a married man." In 1917, on the day he sailed for his second tour of Japan, Art filed for divorce.

On his return to Japan, Art was again treated like royalty. Thousands turned out to see his shows. One newspaper estimated some seventy thousand spectators witnessed the Oyama exhibition. The paper reported, "Ten thousand soldiers from regiments in Tokyo attended the flight in a body, and lined in front of the enclosure making a human fence against the pressure of the public standing ten and twenty rows deep."

Art's two trips to Japan brought many money-making opportunities. On one occasion it was reported that Art would net between seven and eight thousand dollars for his tour in 1916. During his return visit the next year, newspapers commented that many Japanese businessmen were approaching him with offers to acquire the rights for his patents and that there was talk of establishing an Art Smith Company in Japan. But Art was no longer concerned with making money; he was more interested in flying exhibitions and in entertaining.

Any notion of continuing the status quo quickly came to an end, though. As war spread through Europe in the years preceding 1917, Art had become a spokesman for American preparedness. He believed there was a need for the United States to train and equip pilots in case of aerial battle. He turned down requests from several countries to teach aviation and said when the United States needed him, he would be available. After the United States entered the war in April 1917, Art left his stunt flying and exhibitions and tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps. Some said he was refused because he was too short, others said it was because of the effects of many crashes. Instead, Art was assigned to train and test pilots. From 1917 until 1920, at different times, he was stationed at Langley Field in Virginia, Carruthers Field in Texas, and Wilbur Wright Field in Ohio.

After the war, Art did not resume his celebrity tours, but he did continue flying. In 1923 he joined the U.S. Air Mail Service, piloting the Chicago-to-Cleveland route. One night in 1926, while on his mail route, Art encountered fog and icing conditions between Waterloo, Indiana, and Bryan, Ohio. He must have mistaken the lights around a Montpelier, Ohio, farmhouse to be field lights, and by the time he realized his mistake, it was too late. He tried to turn, but in so doing, he flew into a patch of trees and crashed, cutting a swath some two hundred feet through the woods. Authorities could not determine whether Art died in the crash or in the subsequent fire.

As people learned about the crash, shock and grief spread throughout the world. Even the Emperor of Japan sent a telegram asking if it were true that the "Bird Boy" had died. Fort Wayne residents wanted to honor their hero, but Art's mother decreed there would be no funeral service. Eventually she relented and allowed a Christian Science service. Art was buried in Lindenwood Cemetery where Lieutenant Paul Baer, his friend, would later be buried.

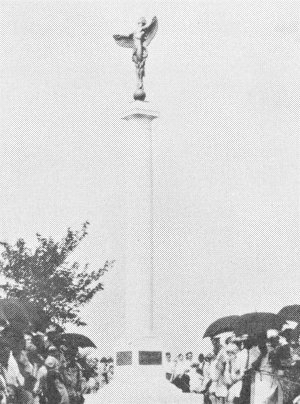

After his death, the city of Fort Wayne placed in Memorial Park a monument to honor Art Smith. Designed by James Novelli of New York, the monument includes a forty-foot shaft of Vermont granite. Atop the shaft sits a bronze statue of a youth with wings and a flying helmet, face looking upward, with feet barely touching a small globe. Years later, the city also renamed its first municipal airport Smith Field to recognize the achievements of its famed "Bird Boy."

Memorial to native son, Art Smith, Fort Wayne, Indiana. |

Today a replica of one of Art Smith's early planes hangs in Fort Wayne International Airport. As visitors look at its fragile wings and wires, many shiver to imagine how daring it was for the young boy with the flashing smile and charismatic personality to fly. Those who know his story, however, understand how strongly Art's dream drove him to succeed-and they can appreciate the sacrifices he and his family made to advance the field of aviation and to give thrills to thousands of fans around the world.

Rachel Roberts, a former columnist for the Auburn Evening News, has written a children's book and several plays. Her article "The Club with a Reputation: A History of the DeKalb County Boxing Club" appeared in the spring 1997 issue of Traces. She would like to thank Hubert Stackhouse and Herb Wertman, as well as Roger Myers of the Greater Fort Wayne Aviation Museum, for helping her research Art Smith's story.

Copies of the article are available for $5.00 plus shipping

& handling. Call (800) 447-1830 or

write History Market, Indiana Historical Society, 450 W. Ohio St.,

Indianapolis, IN 45202.